Five Notable Noxious Weeds – The Staggering Reality at Hand

Imagine a shade tree that’s free, never needs water and will never die. Too good to be true? Yes, it is.

This is known as The Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) and it’s a widely distributed noxious weed. The ensuing text presents five noteworthy noxious weeds growing on Colorado’s Front Range. As evident with these five weeds, the public attitude towards weed management must evolve to reflect the staggering reality at hand – invasive plants have spread globally and some of these plants have very particular adaptations that are highly detrimental to native ecosystems, naturalized ecosystems and (even) human health. Landscape architects, property owners and the public must respect noxious weed classifications in order to confront the problem.

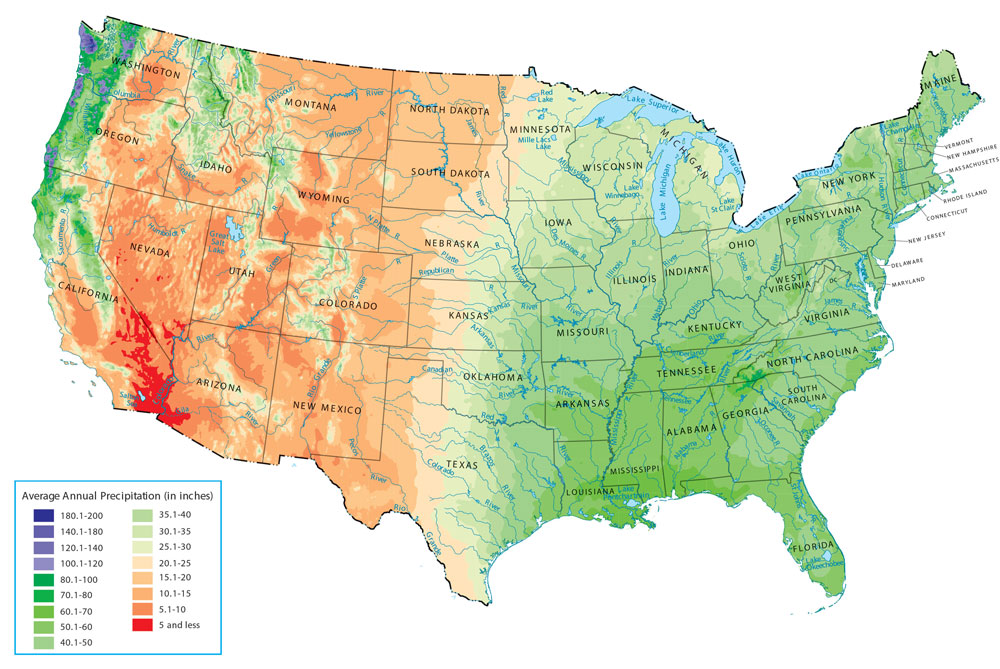

What’s a weed? The simple answer is that one man’s weed is another man’s treasure. This topic is stacked with semantic complexities. The term ‘weed’ is used to subjectively describe undesirable plants. This definition is flimsy – like a plastic bag blowing in the wind. An ecological interpretation contends that most weeds are ruderal species, which appear in high-productivity environments with high levels of disturbance (Beck, 2013). They pop up when conditions allow & devote all energy to seed production. These plants colonize disturbed land & are eventually overtaken by larger species. Weeds that mature into shrub or tree form are merely invasive. Invasive plants are introduced into an environment where they did not evolve. They are highly successful, to the point where they outcompete native plants. In other words, they found a new home with similar conditions to their old home. Invasive plants range from ruderal weeds to large shade trees and they are highly influenced by location & climate. What’s invasive in California will probably not be invasive in New Hampshire, though some noxious weeds are adaptable enough to span vast geographic regions. ‘Noxious weed’ is a legal term that cuts through layers of ambiguity. If it’s a noxious weed, then, yes, it’s a weed – and you should eradicate it! The State of Colorado considers noxious weeds to be:

- Aggressive invaders that are detrimental to the economy & native ecosystems.

- Plants that can poison livestock.

- Carriers of detrimental insects, diseases & parasites.

- Plants that are detrimental to the sound management of natural or agricultural ecosystems.

The spread of plant material by sea-faring Europeans during the 18th century was a landmark shift in global ecology. Previously, plant populations were very localized. Now days, mass disturbance and plant migration have imperiled native ecosystems – as demonstrated by the flowing weeds, which are all non-native, invasive & noxious But first, a few mentions are in order.

- Noxious weeds are classified by the government as a matter of policy.

- They are classified as type A, B, C, with A being the most harmful.

- Noxious weed management requires specialized knowledge and techniques.

- Noxious weeds are highly adaptable and competitive due to adaptations picked up from their native habitat over thousands of years.

- They lack natural controls from their native habitats (insects, pathogens, etc.).

- Noxious plants come in all forms: annual, perennial, vine, shrub & tree.

- The remedy for non-noxious weeds is a non-lazy individual with two hands, two feet & the ability to visually differentiate.

- Most non-noxious weeds DO NOT require an herbicide! Just pull them before they flower.

Type A noxious weeds are designated for eradication by the Colorado Department of Agriculture (CO DOA, 2024). These next level super weeds include Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) – one of the most invasive plants in the world. It was taken from the slopes of a Japanese volcano and brought to Europe during the mid-1800s. It has spread worldwide and has been found in at least 12 Colorado counties. The plant is so prolific that it can grow through asphalt and even into buildings. Why? Because it adapted to the extreme conditions of its natural environment – volcanic islands. It has adapted to massive disturbance and is the first plant to recolonize the volcanic moonscape post-eruption! If you have this plant.. refer to expert advice for removal. Godspeed!

Type B weeds are included in Colorado Department of Agriculture noxious weed management plans – which intend to eradicate/contain/suppress their continued spread. Russian Olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia) illustrates this category in Colorado. Like other invasive plants, it was installed with legitimate intentions, windbreaks in this case, but it quickly became detrimental to the native environment. Often found in riparian zones up to 8000’, Russian Olive is highly adaptable – it is tolerant of shade and poor soil. In Colorado, they stress native riparian zones, outcompeting cottonwoods and willows (CO DOA, 2014).

Type C weeds are included in state noxious weed management plans, but their elimination is not a goal. Instead, outreach and education are program goals. Prolific urban weeds in our region are typically Type C and include the Tree of Heaven, Field Bindweed and Poison Hemlock – among others. These plants are widespread and their complete elimination is impossible. If you live in the Denver metro area, you have seen them. The Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) is the quintessential urban trash-tree. Originally from China, this highly adaptable tree can grow 9 feet in a single growing season up to mature heights of 40-50’. If cut, the tree responds with a myriad of suckers (cut off one head and five grow back). It unsurprisingly produces thousands of seeds and also spreads by rhizome. It can be eliminated with the application of glyphosate to a freshly cut stump. Another worthy mention goes to European Field Bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis) – the ultimate yard pest. It is thought to have originated as an imported seed contaminant (NPS, 2009). Also known as morning glory, it is highly adaptable and aggressive. It’s ubiquitous white flowers can be found growing within your bluegrass lawn, flower beds and anywhere else with soil, light and water. It’s a perennial vine that reproduces via seed and creeping roots (NPS, 2009). Much like the Tree of Heaven, Bindweed does not like glyphosate and 2-4-D, but this method only works while the plant is actively growing. Best of luck getting rid of this one.. The final type C noxious weed killed Socrates and is known as Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum). It’s highly adaptable, but prefers riparian areas, producing thousands of seeds from white flowers. There’s enough coniine within 6-8 leaves to invoke respiratory paralysis and death (USDA, 2018). Other mammals are also at-risk including canines and livestock. On the Front Range, it is found in thick stands with carrot-like leaves and white flowers. It can be eliminated by chemical and mechanical means. Be sure to wear PPE if interacting with this plant! It is highly toxic!

So, what do we do about it? The prevention of noxious weeds by homeowners and commercial property managers requires knowledge and effort. If the government considers a plant noxious, it should be eradicated before it flowers and disperses 180,000 seeds that last for 100 years (Mullein!). It doesn’t matter how pretty you think it is. Weeds, regardless of their classification, thrive with neglect. At the most basic level, human development is disturbance and disturbance generates weeds. Limit disturbance as much as possible and preserve native habitats. Be careful with imported fill; it might be stacked with weed seeds! Pay attention and guide your landscape in the right direction. Learn how to eradicate these plants. It’s not as simple as you might think. Many of these plants have extensive root systems that will reshoot in perpetuity. Herbicides are massively overused, yet they are an extremely useful tool in this fight. Use them sparingly and safely! We’ve significantly altered the earth and it’s our responsibility to mitigate the damage! At the end of the day, just be glad you don’t have Japanese Knotweed growing through your floorboards.

Landscape architects (LAs) are part of the problem and the solution. LAs manage a larger scope than just plants, but typically develop plans to replace existing vegetation with proposed vegetation in accordance with code, client, budget, site, etc. Intentions are benevolent, yet ideas turn into plans, which turn into commercial shopping centers, homes, parks and so on. Landscape architects, in a sense, perpetuate ecological disturbance, opening the door for colonizer species (aka: Weeds). Of course there’s a plan to avoid this, which is one reason landscape architecture exists in the first place. It’s critical for LAs to identify existing noxious weeds on a project – so they can be eliminated before breaking ground. Many noxious weeds have deep roots, allowing them to survive extreme disturbance (like a construction project). Landscape Architects employ a myriad of techniques to manage plant competition and succession. They are highly trained individuals, but more can be done. They can advocate for limited disturbance to native landscapes. They can design native landscape zones on the site periphery. They can stipulate proper maintenance for native grass. With landscape architecture, this goes beyond noxious weeds. Are business incentives and ecological stewardship mutually exclusive?

* This was not written by an ecologist, policy maker or certified pesticide applicator. Nor was it written by an official landscape architect. Seek expert advice elsewhere before making any drastic decisions! Your local CSU Extension Office is a good place to start.

Work Cited:

(Photo1) – ODG Author

(Photo 3) – https://japaneseknotweedagency.co.uk/jkwa_faqs/can-japanese-knotweed-grow-in-or-damage-cavity-walls/

(Photo 4) – ODG Author

(Beck, 2013) ‘Principles of Ecological Landscape Design’ by Travis Beck. 2013. Published by Island Press.

(CO DOA, 2024) https://ag.colorado.gov/conservation/noxious-weeds/faq

(USDA, 2018) Poison Hemlock – https://www.ars.usda.gov/pacific-west-area/logan-ut/poisonous-plant-research/docs/poison-hemlock-conium-maculatum/

(NPS, 2009) – https://www.nps.gov/articles/field-bindweed.htm

This is the official blog of Outdoor Design Group, Colorado Landscape Architects. For more information about our business and our services, click here.